And now I arrive with some trepidation at the most vivid, confident, musical, beautiful and baffling of the films I’ve seen at this festival–Claire Denis’ L’Intrus (“The Intruder”), which has violently confounded and divided movie-lovers here.

When all is said and done, there is a line carved in stone between the world of narrative cinema (that which tells “stories”, however sketchy, and nods at some sort of dramatic closure, however open or provisional) and the world of avant-garde (or so-called “poetic” or “experimental” or “non-narrative”) cinema.

Of course, there are scores of films that contain avant-garde elements in them (like the gorgeous kaleidoscopic transitions that PT Anderson used in Punch-Drunk Love) just as there are plenty of avant-garde films that use narrative (like the psychodramas of Maya Deren).

But ultimately, I would argue, we impose upon a narrative film an obligation to somehow honor its story enough to give it some sense of a dramatic arc, some kind of resolution, some hint of motivation.

But is it really fair to place this burden upon narrative films given that we would likely not bring the same pre-conceptions to an avant-garde film, and that we would almost certainly give the avant-garde film a lot more leeway (it is an “experimental” movie, after all!)?

L’Intrus is narrative in that it contains characters and some semblance of a story, however foggy. It is avant-garde in every other way.

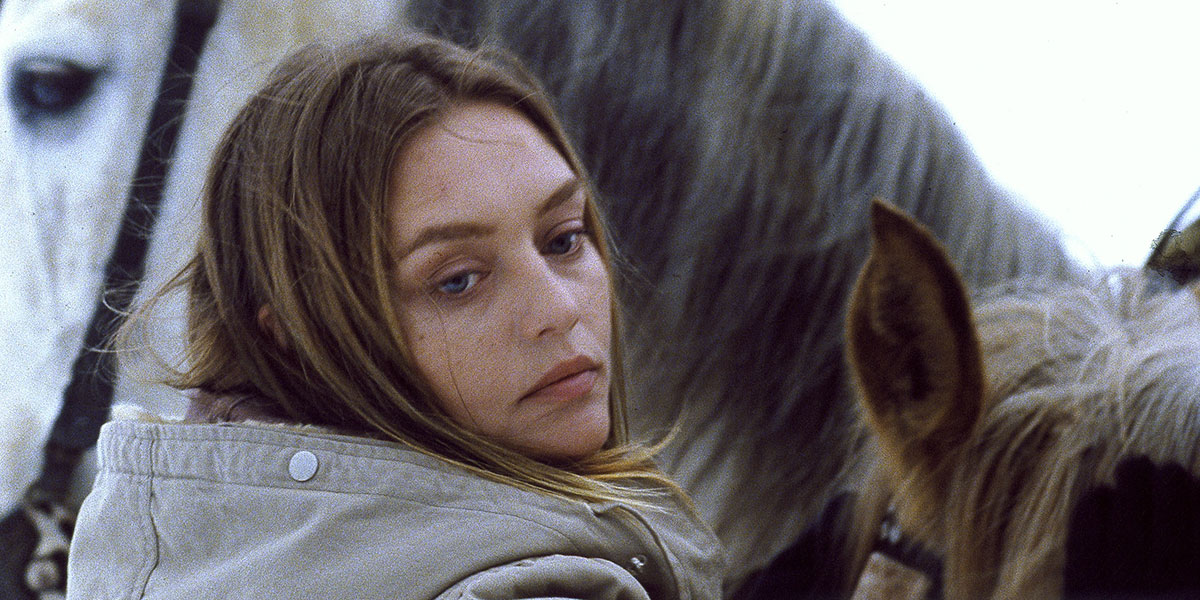

Claire Denis is a filmmaker who has an eye for the rich physical geography of people (their physical characteristics, the way they move, or sit still, or the way they do the minutest, most ordinary things) and of places, both interiors and exteriors. I also believe that she cuts with a fluency and surprise unequalled in movies today.

Thus, in L’Intrus, the narrative recedes in importance, a merely loose framework on which to lay the hypnotic, tactile flow of what is really a savage, tender film-poem.