A striking Arab feminist film series, full of rarities from the past, is being hosted this month by the Block Cinema of Chicago. The series is titled “Liberating History: Arab Feminisms and Mediated Pasts,” and is curated by Simran Bhalla and Malia Haines-Stewart. Two online screenings have already taken place, with three more to come.

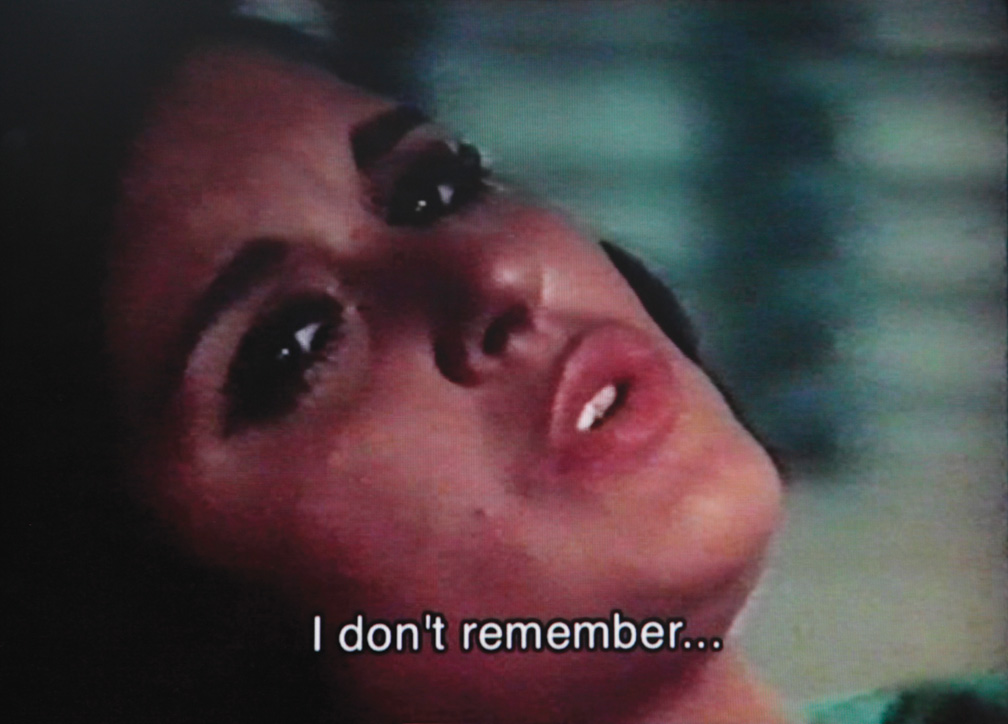

I have not been able to stop thinking about last week’s film, The Three Disappearances of Soad Hosni (2011), by Lebanese director Rania Stephan. Tantalizingly hard to define, it is a found-footage film, an experimental biopic, an essay-portrait suspended between fiction and documentary. Soad Hosni was an iconic Egyptian star who made 82 films, spanning the 1950s to the 1990s—a period that largely overlapped with “the golden age of Egyptian cinema.” Stephan obtained VHS tapes, often pirated versions, of all but 4 of those 82 movies, using them to construct her film over a period of a decade.

Three Disappearances is a powerful feat of montage. By editing together fragments from scores of films (melodramas, comedies, and musicals) in which Hosni appeared, it puts these films—along with their characters, settings, themes and time periods—in sustained conversation with each other. Occasionally, sound and image are detached such that dialogue or music from a certain film infiltrates and haunts another. Characters played by Hosni speak to each other across films and decades. Images and sounds from her filmography become cards in a deck, reshuffled and re-narrativized.

The new narrative that Stephan conjures is both broadly political and sharply feminist. The film is structured in three acts, the end of each act loosely marked in time by a war: the Six-Day War of 1967, the October War of 1973, and the 1991 Gulf War. The first act is often hopeful and promising—Hosni sings and dances, and declares on the street, “We are children of the revolution!” (Cut to posters of Gamel Abdel Nasser, whose socialist government came to power following the Egyptian Revolution in 1952.) The second act displays the expansive variety of women Hosni represented in her screen roles, and the third leads us into patriarchal hell: scenes of male fragility, cruelty and violence both emotional and physical. In one chilling segment, a husband pushes his wife (played by Hosni) to her death from a building, with their traumatized child a witness.

It proves to be a tragic portent of Hosni’s own demise, years later. The actress fell to her death, at the age of 58, from a high-rise building in London in 2001; the suspicious circumstances surrounding the event were never clarified. Hosni’s career had ended 10 years earlier, coinciding with the decline of the once-powerful Egyptian film industry, now starved of state support and eclipsed by the rise of satellite television. Stephan has said that the film operates as “a kind of pre-vision of the tragic destiny of this actress.” And yet, Hosni and her voice have continued to reverberate over the decades. Her song, “I’m going down to the square,” became a sort of anthem and a hashtag for the young protestors of Tahrir square during the events of the Arab Spring in 2011.

The Block cinema series kicked off with Heiny Srour’s classic Leila and the Wolves (1984), a bold time-traveling work that rewrites history by centering the role of women in Palestinian liberation struggles throughout the 20th century. Both screenings so far have been accompanied by extended recorded interviews with the directors. This week’s movie—which will remain available to watch for a 24-hour period beginning at 8 PM EST this evening—is Selma Baccar’s feminist essay film Fatma 75 (1975), the first non-fiction feature made by a Tunisian woman, and banned in that country until recently.

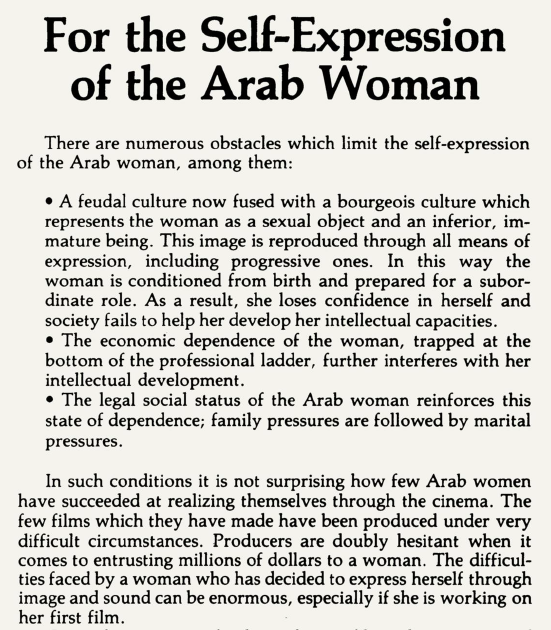

Digging through old issues of Cineaste recently, I turned up a special issue devoted to Middle-Eastern cinema from 1979. In it was a manifesto co-authored by the above directors, Srour and Baccar (along with Arab cinema historian Magda Wassef), establishing an assistance fund for Arab women filmmakers. Its opening paragraphs resonate movingly more than four decades later:

The last two screenings in the series look wonderfully promising too: comprised of short films from Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia, and their disapora. The programs are titled “Present Futures: Sci-fi and Social Ecology,” and “Inherited Memory: Blood Runs Thicker Than Water.” They are curated by Róisín Tapponi of the Habibi Collective.