I’ve had a couple of different trains of thought running through my head lately; let me draw them together in this post under the broad, common theme of auteurism.

The subject of Adrian’s new column at Filmkrant is the screenwriter/auteur debate. He recounts an exchange between Josh Olson and Brad Stevens. Olson wants to remind everyone that even though Cronenberg might get the credit for the two much-talked-about sex scenes in A History of Violence, he (Olson) is the one who scripted them word by word. Adrian writes:

Stevens fires back with an impeccable cinephilic example. The opening scene of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumière (2003) is so rich and complex on the level of its sounds and images, gestures and spaces, light-values and rhythms, that it could never have been entirely ‘foreseen’ or described in a script. Stevens does not mention Hou’s close longtime script collaborator, celebrated Taiwanese novelist Chu Tien-wen, but his point is solid. However, it sends Olson and his LA-based comrades into apoplectic fits: it’s a critic’s fantasy! Auteurist nonsense that can only believed by eggheads who have never made a film! Give the greatest directors in the world a blank page, and see if they are so great then!

As Steven Maras argues in his forthcoming Wallflower Press book on screenwriting, this rage rests on the metaphor-idea that, while the writer is the true creator, and the script functions as an architectural blueprint, the director is merely the person who ‘executes’ the script, or builds the house to prior specifications. What auteurism – in its most enlightened form – is about is not the god-like primacy of the director on set, but the ‘holistic’, integrated, organic conception of a film, from first idea to final post-production. Hou guides this process from the start; while Cronenberg imposes his vision on projects that he does not always initiate. But cinema is the weaving of many different ‘writings’, from the written to the filmic – not the primacy of any one over all the others.

The above piece sparked an interesting discussion in the comments to the previous post (scroll down about three-quarters of the way). I thought we might continue and extend it, either here or in the previous thread. Let me offer a few remarks in response to that discussion.

In my view, auteurism is not an account of how films are made. It is instead one among many ways we, as viewers, choose to read a film. In other words, it is one particular lens through which films can be viewed: by foregrounding the ‘marks’ of expression belonging to one person, the auteur, most frequently the director.

The first widespread use of the term in France in the ’50s occurred in a very specific historical and political context. Cahiers du Cinema critics used their politique des auteurs to champion those filmmakers working in the Hollywood system who managed to imprint their signatures on films being made within a factory-like system of production. Thus, the CdC critics chose to read Hollywood films—and this was a political choice they were making—in a way that focused on the ‘identifying marks of expression’ made by an auteur like Nicholas Ray or Alfred Hitchcock or Howard Hawks.

Since then, the term ‘auteur’ has found use in a looser, broader fashion, but I don’t see it as objectively claiming (as a ‘theory’ might) that the contributions of the director trump those of the screenwriter, the stars, the cinematographer, etc. In fact, the term ‘auteur theory’—first used by Andrew Sarris when the politique made its trans-Atlantic crossing in the early ’60s—is misleading since auteurism is not a theory at all, but instead a certain mode and manner of reading films.

Dana Polan has a fascinating essay called “Auteur Desire” which was published at Screening the Past in 2001. He explains the double meaning of the essay’s title:

On the one hand, in auteur theory, there is a drive to outline the desire of the director, his or her (but usually his) recourse to filmmaking as a way to express personal vision. The concern in auteur studies to pinpoint the primary obsessions and thematic preoccupations of this or that creator is thus an attempt to outline the director’s desire. On the other hand, there is also desire for the director – the obsession of the cinephile or the film scholar to understand films as having an originary instance in the person who signs them. Here, it is important to look less at what the director wants than what the analyzing auteurist wants – namely, to classify and give distinction to films according to their directors and to master their corpuses. […]

[There is a] belief in conventional auteurism that it is precisely because the pressures of the system so weigh down on the auteur that he/she (but usually he in the canons of such criticism) is forced to creativity as a veritable survival tactic.

Polan makes a distinction between ‘classic’, Cahiers/Sarris auteurism and contemporary auteurism. The former was frequently mystificatory, believing that “personal artistic expression emerged in mysterious ways from ineffable deep wells of creativity,” while the latter involves closer attention to the encounter between the auteur and the resources of filmmaking, and

a greater concreteness and detail in the examination of just what the work of the director involves. Gunning, for example, is explicit in his understanding of Lang not as a romantic genius drawing inspiration intuitively from hidden depths of insight but as a veritable pragmatist who directly labors on the materials of the world.

Likewise, the historical poetics of David Bordwell focuses attention on the immediate craft of the filmmaker – how he/she works in precise material ways with the tools and materials of his/her trade.

There are precursors to these contemporary approaches: for example, the mise-en-scène criticism of Movie magazine and V.F. Perkins, and Manny Farber’s close attention to the myriad ‘surface’ details of a film—what Polan calls “an auteurism of energetics rather than metaphysics or thematics.”

He also proposes this interesting idea:

[I]t might not be too extreme to suggest that in the auteur theory, the real auteurs turn out to be the auteurists rather than the directors they study. Faced with the vast anonymity and ordinariness of the mass of films that have ever been made – and in contrast to the anonymous, ordinary manner in which many people see films (the LA times reports that many average spectators go to the multiplex not having a specific film title in mind and choose once they confront the array of offerings) – the auteurist quests to have his personal vision of cinema emerge from obscurity. He struggles to impose his vision on a system of indifference…

This brings me to a notion that I have long wondered about: why is it that seasoned, intelligent auteurists don’t always agree on the value of a particular film or filmmaker? In the light of “auteur desire,” the answer is not difficult to see. If each auteurist brings to and imposes his/her desire upon a film or filmmaker, and no two people share the exact same configuration of desires (assuming that the desires of a person are influenced by his/her ‘subjectivity’, which is historically shaped by the accumulated set of cultural experiences that person, or ‘subject’, has had), each person would, naturally, have a different and unique encounter with a particular artwork. This makes disagreements both a matter of course and perfectly understandable.

Dan Sallitt, in a thread from the a_film_by archives, offers interesting insights on disagreements about the value of artworks:

When we disagree about the value of an artist or a work of art, we wonder how intelligent observers can be so far apart, not only in their opinions, but also in their perceptions. One possible model for disagreement is that one person has a wiser perspective on the topic at hand, and that the other person simply has grabbed hold of the wrong end of it. In most cases, this model is deeply inadequate from any objective perspective: it doesn’t account at all for the great coherence and thoughtfulness that we often see on both sides, even when the positions are plainly mutually exclusive. But, in our hearts of hearts, this is the theory that we usually hold when we are one of the parties to the disagreement: our own position seems so coherent that we suspect the wisdom or the motives of the other party. Once in a while life presents us with an example of a disagreement where one side is clearly better supported than the other, and these occasional instances give us hope that maybe all of our opponents are similarly misled.

What occurred to me this morning is that maybe we underestimate: a) the incredible amount of data available in even the simplest work of art; and b) the mind’s ability to find strong, coherent patterns in even a small collection of data. So, for instance, I come to Kubrick with a particular heightened aversion to a certain acting style which is connected to a certain personality trait. I identify this element, am ticked off by it, and calibrate my perceptive apparatus so that I start picking up any other element with some aspect in common. Because there is so much data in a movie, I have no trouble finding lots of support for my initial aversion, and in discarding the occasional data point that doesn’t fit what I’m looking for. Within minutes, voila! I have constructed a coherent Kubrick-pattern that I call a sensibility. Meanwhile, other observers, without the same baseline aversion that I have, not only construct a different Kubrick-pattern, but also lack a slot in their Kubrick-pattern to help them identify the traits that look obvious to me.

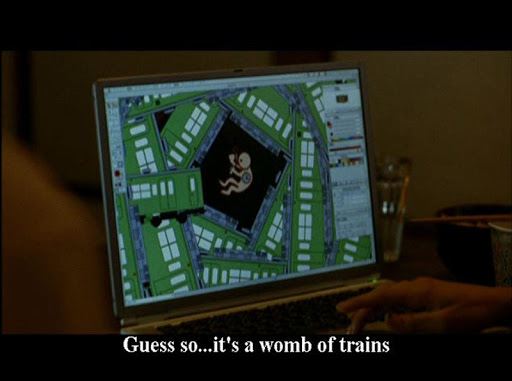

pic: The train animations from Hou’s Café Lumière.

nitesh

March 31, 2008 at 10:58 am

Girish, as usual a wonderful post: mixed with your regular dose of collage and insights. Their something about Auteurism, I have never been able to grasp or understand completely, in the midst of all this theories and definition and judgment, the silver lining between an auteur and craftsman is something which I haven’t been able justify and collectively understand (presumably this has to do with my lack of insights and navieness about the medium). The title of the current post reminded me of a class on, “Film Appreciation” in college, my teacher who in mist of being an FTII graduate was far vocal and pessimist against all the auteur theory- and she had her set of reason, though definitely not as critical, as we don’t have a base or foundation of a genetic pool of critical study here in India.

The question hence raised was: Is Karan Johar, Rituparno Ghosh as much an auteur as the people you champion (here she referred to the bunch of young left cinephile from East India like me). The debates went on for days: yes, the discussion was interesting but in the end: no conclusion was ever reached. After all, if Mirnal Da, Or Buddadeb Dasgupta: Writes, Direct, and forms a visual idiom and syntax of their own which can be traced from films to films, which also is true for a film of Karan Johar or Rituparno Ghosh. So what then makes the thin distinction between a commercial filmmaker like Karan Johar, a semi-art filmmaker like Rituparno Ghosh and the likes of poets like Buddadeb Dasgupta?

A couple of months back I was interning on a film, which was to be, ‘ different’ in all its form for the Indian market, to certain extern it was, Dil, Dosti, etc. But the director never got his due. I remember when he said, I’ m trying to work towards certain sensibilities of the French New Wave, the unanimous reply was you have two choice : Get out of the film or make it the way we want( a major portion was re-shoot again). Since theories and stuff no one believes or gives damn. The only moment when such talks of theories are fine, it’s behind closed doors. The major distinction for our, ‘Media’ are, ‘Realistic’ filmmaker and, ‘Non-Realistic’ filmmaker. The fact India is a country which produces one of the highest number of films in the world, and has an audience whose apettite for films are not going to decline any time soon- I wonder how much of all this autueurism really is important after all, since, most people really don’t get it. I guess a certain pool of real critical and mainstream study is required here.

It’s always an immense pleasure reading the blog, and the comments which proceeds especially with the likes of Maya, Harry and others there is an immense joy in learning. Sorry, the post got a little long, but I believe this is an important place of discussion, and in all my navity I think it’s important for the people of our generation here to be in touch with major critical analysis from the world, and thank god, the Internet has really helped. Else I wouldn’t have got a pat behind closed doors discussing Cinema with some important filmmaker, after, they were not aware what happens in the world beyond their own small world or what they had seen Film School, but Critical standpoint nil. Though while leaving they said: ‘ Beta, it’s nice yeh theories, ye all this, par French New Wave and tumhara critics, film nahi banathe hai, so you better leave all this make some films, in our Indian tradition and later you can do experiments.

(Son, all this theories are nice- French New Wave and this critic , but they don’t make films, so you better leave all this, and first make films our ways: then you can experiments)… Cinema is about storytelling, was the unanimouous agreement with most people, rest sab bakwaas hai (Rest everything is crap). Well, at least I dint’ believe any of this.

HarryTuttle

March 31, 2008 at 11:44 am

This old debate pre-dates the existence of cinema. It’s the conflict between “art criticism” and “reader’s response”, one looks at the generation of the artwork inside the artist’s inspiration (and the way its coherence spans the entire oeuvre), the other looks at the final result, an object out of context, as perceived by the emotional sensibility of one certain witness (one film at the time, and only what is seen on screen). They operate on a different level and don’t really contradict each others because they don’t focus on the same thing at all.

I agree auteurism is one way to analyze an artwork but we could hardly ignore it entirely if we consider cinema an Art equivalent to Literature and Painting. La Politique des Auteurs did more than just offer a new perspective on Hollywood, it changed the status of cinema (in general), from an industrial spectacle made by a team of industrials to a personal art made by an artist. If there is no artist at the origin of the work, there is no Art.

Now the fact that only one interpretation of an artwork could exist is a common misconception. Nobody argues that in Literature, various art critics could offer differing and complementary readings of a poem, most of which would even elude the poet’s consciousness. A poet puts a lot more than (s)he is aware of intentionally consciously generating when spontaneously inspired, and theoretical frameworks can help to extract the hidden symbolism, the subconscious desire, the rhythmic patterns. If the poet herself is not aware of it doesn’t mean it is an invention of the analyst, it doesn’t mean that the poet’s own interpretation/explanation of her work is the only valid one. But if these interpretations are soundly constructed and significant they converge toward a particular perception of truth, because a critic’s subjectivity is formed from the same general patterns than another critic or the artist himself. We are all humans that’s why we can share emotional experiences and that’s why certain pieces of Art may resonate universally with mankind (beyond individual subjectivities). We don’t know why an artwork makes such a powerful consensus within the population and throughout ages (beyond fads), and that’s the critic’s job to figure it out (with the help of tools the average witness is not conscious of).

But the critic is just a human like any other witness, and therefore cannot entirely escape the projection of his/her own subconscious desire onto the object of study. This is the reason why people mistrust “theoretical objectivity” while this uncertainty is part of the equation, and still connects with the “collective unconscious” : if our very personal fantasy is triggered by a stimulus, it wasn’t put there by chance, and most likely this pattern also resonates with what the artist has put together (whether consciously or unconsciously), because we all react to the same archetypes.

p.s. Thanks Nitesh. It’s the collective discussion and mutual sharing that is priceless here. 🙂

Anonymous

March 31, 2008 at 3:30 pm

Perhaps it is oversimplifying things, but I look at auteurism more as an interpretative context rather than a theory of production/creation/intention. I use it as a critical tool to find consistency, continuity, and patterns (or their absences) to better understand a film or group of films, hopefully in a similar way to understanding the historical context or industrial context.

Brian Darr

March 31, 2008 at 7:22 pm

That’s the logic behind my own “autuerist philosophy” too, daniel. But I must admit that sometimes I notice myself lazily slipping into a shorthand when talking or writing about films, in which the words I’m using seemingly imply that the director is also paramount in creation and especially intention. I can see how this shorthand would frustrate some people, yet it’s almost necessary if I don’t want to start each conversation with a disclaimer.

I read the entire exchange mentioned in Adrian’s column, and I found it interesting that Brad Stevens never really qualified his comments with statements like girish’s “auteurism is not an account of how films are made. It is instead one among many ways we, as viewers, choose to read a film.” He did speak to the difference between being interested in studying the filmmaking process and studying the work itself, though- perhaps this is roughly equivalent.

I can see why Olson would have grown so frustrated with auteurism and want to stamp it out in all its forms. Clearly some people misinterpret and misapply the tool, and I have no reason to disbelieve when he rails against the influence the director-as-auteur concept has in Hollywood. I wish I could be optimistic that the general perception of the director’s actual role in filmmaking could become better-informed, without the abandonment of a highly useful way of looking at and speaking about films. But I’m afraid that it may be too late for that- that what comes to most minds when the word “auteur” or “director” appears is already impossible to dislodge.

Anonymous

April 1, 2008 at 1:37 am

I’m rather old-fashioned when it comes to my appraisal of whatever it is that we may call “art”. I use the New Critical framework of “the artist is dead” so that I don’t, say, proclaim a poem a “great poem” simply because I know it was written by Sylvia Plath. So most of my appreciation of any artform undergoes this movement of consideration: the art object first and the artist second. Of course, there are always exceptions, but for me the most important is that I appreciate the object first. That said, it’s obvious I don’t abide by the notion that “a lesser work of an artist is more worthy than the superior work of a mere craftsman”. Art is in itself the result of craft.

I’ve been reading the a_film_by archives as well, particularly the posts about auteurism, and I find myself sympathizing with Dan Sallitt’s view on auterism (that his critical outlook is not solely dependent upon it). I firmly believe that film is a collaborative art that is produced by the interaction of various creative forces (directors’, actors’, screenwriters’, cinematographers’, art directors’, costume designers’, etc.) because, well, simply put, that is how film is made in reality. It’s easy to apply auteurism to literature because there is the writer alone in direct contact with the pen, paper, keyboard, computer. There is one mind at work. All the words and metaphors come from this single person. But the film crew is not composed of brainless objects but rather human minds that are constantly creative. People do not stop thinking (unless they are dead). The vision I see on the screen is a vision that is the result of all these creative forces at work. I guess the director is able to “direct” these creative forces into a comprehensive vision that we see on screen, but that doesn’t mean he is the sole artist of the work. That’s a bit too fascistic for my tastes (unless he is directly responsible for the minutiae of every process – art is in all the details). Whenever I’ve sat in and watched people making a film, it’s always struck me how much it is a collaborative process. I guess the narcissism comes after. (Not to name names but a young Philippine director du jour in the Senses of Cinema World Poll comes to mind).

Anyway, I wonder why the work of a single creative mind is usually prized above the work of several creative minds? If in literature we are able to accept exquisite corpse and renga as valid art, why not artwork that does not possess a single “auteur”? What about the Dardennes, Coens, or Quays? Surely we grant each of the brothers their individuality and thus their individual creative obsessions, processes, etc., and that their films are results of multiple creative forces at work? Or what about that for something to be deemed as art, that it is entirely possible that the creative force behind it isn’t even identified in the first place (I’m thinking of Beowulf or the Bhagavad Gita) If this is possible in the auteurism of literature, then I personally believe that auteurship in film is never limited to the director alone, or that such ascribing is even necessary.

I know, my rationale may be simple-minded, but, heck, I’ve been more than happy sticking to it throughout my cinephilic life so far 🙂

Anonymous

April 1, 2008 at 1:46 am

Girish brings up the point that auteurism is a way of reading film instead. I have no objections to that perspective 🙂 But I myself can’t seem to ignore the fact of how film is made in the first place. I have to know how this art is produced, and then I will know how to approach it, to read it.

Michael Guillen

April 1, 2008 at 4:25 am

I get the sense that there are probably as many theories about auteurism as there are auteurs hoping to fit the theories; much like the ball of a roulette wheel going round and round and round, finally falling into its appropriate chance slot. Of course as W.C. would grumble, “This ain’t a game of chance. Not the way you play.”

I like how Girish has qualified this ongoing debate. Auteurism is not really a theory at all but a way of reading a film! That makes sense. Auteurism would then more pertinently describe the sensibility that informs a film, with the caveat that this might be an energy at work distinct from the director’s vision (which—it seems to me—is how auteurism is popularly conceived). As I’ve mentioned before, Lewton as producer was considered (by some) to be the auteur of his productions, though one would have to be downright blind or misguided or lacking in generosity not to commend the contributions of Tourneur’s directorial flair, Musuraca’s atmospheric cinematography, or Robson’s infamous “bus” (the granddaddy of the startle edit). The auteur’s sensibility or personal sense of style, the way he or she holds the film together, would have much to do with a spirit of collaboration or the lack of it, the willingness to share credit or to not share credit, the overall awareness of what each individual on the moviemaking team has contributed to the final product. So if the lens of auteurism was applied by the French to the film factories of Hollywood, it was to grant credit and credence to whoever gave the gift of cohesion (or as Dan eloquently states it, coherence) to a film and—for ease of interpretation—the director seemed a likely choice, since he (or she) came off like a conductor guiding an orchestra. But as anyone who loves classical music knows, the music doesn’t really belong to the conductor—and extending the metaphor to film—the conductor isn’t always synonymous with the director. Dottie and I are in concurrence here.

As for why one man’s testament to coherence is another man’s messy bedroom has everything to do, I think, with vibration. The ability to sense an affinity or to understand another’s intent is the gravitational pull—the recognition you might say—of their sensibility. Films, like paintings, like any image for that matter, have gravitational fields. In some instances even magnetic fields. They draw you in or deflect. You are either destined to crash and crater, sworn to orbit, or off on the thrust of your own ellipse, as happy and carefree as a comet.

Aside from Polan’s astute forensics that the fingerprints of “auteurists” are all over their auteurs (I think he’s got the ship in the bottle), perhaps the noun should be severed from the individual and given back to the act? Auteurship rather than auteur? That might more readily allow for how two (or more) individuals can “make wonderful music together” (to hammer that metaphor into place). The dyslexia that informed and fractured Guillermo Arriaga’s narratives were given a particular focus and athletic vibrancy by Alejandro González Iñárritu’s directorial prowess. Their synergy created a great internationally-acknowledged trio of films. A comparable synergy was achieved when Arriaga broke off to work with Tommy Lee Jones who likewise flexed directorial prowess. Arriaga’s Night Buffalo, however, lacked some vital thrust. Perhaps the virile synergy of collaboration? And we have yet to see what Iñárritu can do on his own. Though I will say that Iñárritu’s adamant refusal to share his auteurship (banning Arriaga from attending the Cannes Film Festival) is a bit telling. In my book, one can be more generous with what is really their’s.

Again with Dottie, to insist on granting auteurship to single individuals is to beg indulgence of the wisdom of Solomon who will, undoubtedly, blithely advise that you split the baby in half. Some fools just might do it. And judging from some films, some have (Orson Welles comes to mind).

The Polan essay looks intriguing. I’ve printed it out so I can sit down with it in the morning when I’m most alert with coffee at hand and—as an alternate to comprehension—when my remembrance of origami is at a heightened pitch; fold here, fold there, fold here, fold there (sip of coffee). I’ll be back on that, though I must admit upfront that “an auteurism of energetics rather than metaphysics or thematics” just makes me want to sneeze outloud. My sinus cavities can only be tickled by so many “ics” and “isms” before they protest.

Nitesh, thank you for your kind words. Girish’s class is the best, isn’t it? No false dichotomy between teacher and student; it’s all learning here for everyone or—I name no names—not.

Dear Harry: Can I fix you a cup of coffee and teach you some origami? Fold here, fold there, fold here—Harry!—don’t fold there! Heh. I very much like the craft of your paragraph that ends with: “If there is no artist at the origin of the work, there is no Art.” Even if I don’t agree. Workers are the origin of work. Promote them to craftsmen. Flatter them as artists. But workers are the origin of work. Art is something else. Some transcendent interpretive interaction belatedly contingent on no less than a billion variables. Just look how an indigenous artifact, for example, can be converted to art merely by removing the fact and placing it ingeniously in a white cube. Did that Mali dude mean for that ladder to sell for hundreds at Sotheby’s? I’ve been in home interior stores where old propellers, rowing oars, even patent leather clown shoes, leave utility behind and—through form, through shape, through nostalgia’s desire—become invested with the attributes of art. Every now and then some seasculpted driftwood or smoothed touchstone gains an aesthetic currency as consensual as gold.

Interesting you should venture into the archetypal patterns of poetry. I’ve just picked up a second-hand volume with that title by Maud Bodkin published in 1958. I bought it as much for the smell of the paper as for its homage to the biological wealth resident in the human psyche.

Brian, I strongly recommend you begin all your conversations with disclaimers or at least end them with apologies. At least with me. I can’t bear to be any more frustrated than I already am. For starters, I’m not sure if I’m upset with the director-as-auteur approach simply because it has more hyphens than it probably should.

Peter Nellhaus

April 1, 2008 at 5:34 am

Probably the best support for the auteur theory that I read came from a screenwriter. John Gregory Dunne wrote a piece in Esquire as I recall, about reading two unfilmed screenplays. He thought The Great Gatsby was one of the best screenplays ever written, while The Wild Bunch was one of the worst. As Dunne pointed out, it takes more than the screenplay to make a good film.

Michael Guillen

April 1, 2008 at 8:28 am

Conversely, a bad director can ruin the better of two scripts. You’re begging a definition with exceptions.

girish

April 1, 2008 at 1:48 pm

Thank you, Nitesh, Harry, Danny, Brian, Dottie, Maya, Peter!

Maya, your origami examples make me laugh out loud.

Perhaps I can add just a few more thoughts:

— I think auteurism can be very sensitive to issues of craft. Dan Sallitt is a filmmaker with two admired feature films to his credit; he is an extremely sensitive and insightful auteurist, with great knowledge of craft. David Bordwell is an example of an auteurist who has written (his late work, especially) in amazing detail about craft–e.g. his book Figures Traced in Light, about staging practices in cinema, which have rarely/never before been studied with the sustained care and detail he devotes to them here.

— As people, we don’t simply belong exclusively to just one category of art-lover. e.g. I consider myself an auteurist, but I’m not only an auteurist. My recent immersion in Indian popular cinema has shown me that auteurism is quite a limiting way to enter that cinema. Genre and stars are at least as, if not more, valuable ways to personally make sense of, e.g. ’70s Bollywood cinema. So, I often end up foregrounding them more than I do the director.

– For auteurists: Do all the films you like/admire lend themselves equally to a high degree of auteurist appreciation? I wonder what kinds of cinema begin to slowly pull you away from auteurism…?

Peter Nellhaus

April 1, 2008 at 3:22 pm

For myself, it’s not being pulled away form auteurism but recognizing that not all directors are auteurs and not all auteurs are directors. A couple of years ago when Freedomland was released, Andrew Sarris wrote a piece appreciating the work of Richard Price, novelist and screenwriter.

In the case of some of the vintage films from 30’s, I generally like Warner Brothers films no matter who the listed director may be, whether Michael Curiz, Lloyd Bacon or Archie Mayo.

HarryTuttle

April 1, 2008 at 4:12 pm

Like Miguel Marías said in the last post, it’s surprising that of all places on the internet we should argue with auteurism here like it was a whole new conundrum all over again… If we have to go back to the raison d’être of an auteur it’s going to be a looooong debate. Especially since there is more than one issue brought up here. So many problematics are conflated and solved as if there was only one. Not all of them (if any) have the liability to debunk the auteurist theory.

And sure we can watch and love movies without the auteurist theory, without knowing the name of the director, but that’s besides the point. It’s like worshipping a love poem for its intrinsic beauty and forgetting that someone actually made it for you and that the love feeling at the origin of this production is what matters, not the incidental singular incarnation. That love could generate hundreds more of poems alike. If you keep the poem and get rid of the lover your relation to that sentiment is purely fetishist and superficial. That’s the reason why a critic cannot remain a simple blissfully ignorant viewer like anyone in the audience. A critic’s aim is to extract the hidden quintessential desire that made the visible achievements of the film possible.

“Conversely, a bad director can ruin the better of two scripts. You’re begging a definition with exceptions.”

This is a correlation rather than an exception. 😉

“For auteurists: Do all the films you like/admire lend themselves equally to a high degree of auteurist appreciation? I wonder what kinds of cinema begin to slowly pull you away from auteurism…?”

The answer is in the wording of your question, Girish. You oppose “like/admire” to “appreciation”. Not that they are incompatible, but they refer to a different level of approach to cinema. We may love films that have no artistic values and it may be intolerable for us to sit through a film we recognize great artistic values. There is no self-contradiction at all. The “cinephile” (Eros) and the “critic” (Aesthetics) inner conflict to win over your mind. The cinephile doesn’t needs to have “good” taste, there is no guilt or shame to sport bad taste or subversive/peculiar/obsessive attractions. And “taste” is proper to the individual, it no longer applies when we look back at the history of Arts with some distance.

HarryTuttle

April 1, 2008 at 5:14 pm

Dottie,

“a lesser work of an artist is more worthy than the superior work of a mere craftsman”

Being an auteur doesn’t preclude being a bad auteur. It only means having a distinct own consistent coherent meaningful signature.

Now what is your distinction between “artist” and “craftsman”?

“But the film crew is not composed of brainless objects but rather human minds that are constantly creative.”

No disagreement there. Now just compare the scope and depth of each of these individual employees to the impact of the auteur’s creativity.

“art is in all the details”

But details alone, separated from the sum and its transcendence, aren’t as great as the complete work. It’s completion that matters. And the artist can replace a missing detail by another one if an employee fails. The master-artist in control cannot be replaced however, without dramatic changes. Remove the artist from the team of creative minds and the artefact loses its status and value of Art.

New Criticism also ignores how the object was made (intentional fallacy) so the number of “creative forces” doesn’t matter. Your understanding of the word auteur is too literal, it’s an abstract concept for the original generating force authoring the distinctive identity of the artwork (which is more important to Art than its craft materiality). So the “Auteur” could very well be a duo or a team, but a team of auteurs then, not a group of mere creative individuals (who each have no idea of the final achievement of the whole outside of their own contribution).

Take the example of Lynch who keeps the point of his film a secret till the end (and it even remains unknown after projection fo the film). This is a good metaphor for the artist’s vision that is proper to the artist and cannot be shared (even if he wanted to) in words. The artist only knows how things should go and how it shouldn’t be (even if he’s unable to explain it, to predict or to verbalize it). The point is that he knows and that he will control all contributions in order to accomplish this vision. Give a Lynch project to another director, they wouldn’t know what to make of it! This is a dramatic example , but even with simple scripts and easy films, the auteur’s intention is not transmissible.

“If in literature we are able to accept exquisite corpse and renga as valid art, why not artwork that does not possess a single “auteur”?”

Auteurism doesn’t negate “collective artworks”. It’s just a particular case. Usually, the vast majority of art is made by individuals, that why we often take this generalisation as a rule. Auteurism isn’t a numerical rule, it depends on the identity of the signature, whoever authored it.

Anonymous

April 1, 2008 at 5:38 pm

Thank you, Maya, you’ve put into such eloquence what has been in my mind and that I’ve only managed in fractured comments 🙂

Harry,

“It’s like worshipping a love poem for its intrinsic beauty and forgetting that someone actually made it for you and that the love feeling at the origin of this production is what matters, not the incidental singular incarnation.”

First of all, how is disregarding the auteur theory disregarding the fact that the act of creation produced such a work of art? I acknowledge that art must be produced (it did not fall from the heavens!) It just means that I don’t find identifying the source of creation as necessary to appreciating a work of art. No one can identify who wrote the Bhagavad Gita. Don’t tell me it is not a work of art, or that my appreciation of it as a work of art is invalid because I do not know the specific circumstances of its creation?

“If you keep the poem and get rid of the lover your relation to that sentiment is purely fetishist and superficial. That’s the reason why a critic cannot remain a simple blissfully ignorant viewer like anyone in the audience.”

I do not get your point here. How is simply appreciating the intrinsic value of art fetishist and superficial if we are able to be critical about it? Your analogy does not make sense to me. Surely, the highest value of a love poem received is found in the fact that it was given by a lover. But how can you say that filmmakers make their art out of love for their audience in the first place? And how is one ignorant if he or she simply decides to appreciate the object in question with a critical mindset, without any interest in its creator, BUT acknowledges that the artwork has been produced through the process of creation?

How is this a work of art? What are its values as art? These are the questions I ask myself. I don’t necessarily need: how does this work of art fit into the oeuvre of its creator? What does it say about its creator? Of course, that doesn’t mean I don’t ask these questions myself.

“A critic’s aim is to extract the hidden quintessential desire that made the visible achievements of the film possible.”

And for this to happen the critic must without a doubt know who the director of the film is or who its auteur is? What if Mizoguchi had died without ascribing his name to any of his magnificent films? Does that render them valueless as art? Does that render them inferior because of their anonymity? If they were anonymous and yet exhibited sensibilities that made them seem to be related, how can we be perfectly sure about that?

Look at Maya’s previous post. He answers a lot of the questions here.

“The “cinephile” (Eros) and the “critic” (Aesthetics) inner conflict to win over your mind. The cinephile doesn’t needs to have “good” taste, there is no guilt or shame to sport bad taste or subversive/peculiar/obsessive attractions. And “taste” is proper to the individual, it no longer applies when we look back at the history of Arts with some distance.”

More dichotomies? Such a simplistic way of thinking about people. I’d like to think I have more subtleties and nuances about me and that you were referring to me here, indeed, in the first place! So, I say: I am a critical cinephile. I love cinema first, and I am a critic second. Just because I’m a proclaimed “cinephile” does not mean I lack in critical faculties. Stop assuming, Harry.

Taste, such a worthless word. There is no good taste or bad taste, just personal taste. But that’s already a given.

Anonymous

April 1, 2008 at 6:43 pm

Harry, I just saw your post. Must be the difference in time zones!

I’ll admit I don’t know much about auteurism, but I’ve always thought it depended on identifying who the “auteur” is in the first place. Anyway, I like thinking about things simply, so just a disclaimer on my thought processes here, unless you think me some ignorant fool!

“Remove the artist from the team of creative minds and the artefact loses its status and value of Art.”

What? Are you talking about film? Or any artwork that involves creative minds at work? Are you saying that out of these creative minds there must be an artist who stands out, or that these creative minds function collectively as an artist?

Does the status and value of art rely on an artist? What if the artist can’t be identified? I’m repeating myself: the Bible, the Bhagavad Gita, the numerous oral epics, the anonymous art found in museums, etc. etc. etc. Do these works of art need a signature? Whose is it then? The signature of the cultures that produced them? Okay, art is borne out of a process of creation. For me, knowing that is enough.

Craftsmen and artist: I don’t distinguish between the two.

“Now just compare the scope and depth of each of these individual employees to the impact of the auteur’s creativity.”

Is it even possible to know this for sure? How can you say so? People lie about their contributions all the time. Can it be gleaned from the object itself? Who can say if it was Greta Garbo or George Cukor who was primarily responsible for her exquisite maneuvering of space in Camille? Were we actually there when they made the film? There is the dilemma: Greta Garbo moves exquisitely in her other films, and the actors in Cukor’s films move exquisitely as well.

“But details alone, separated from the sum and its transcendence, aren’t as great as the complete work. It’s completion that matters. And the artist can replace a missing detail by another one if an employee fails.”

I never said as much. I just said that art is composed of details. Are you still talking about film? How would you know if an employee fails? Does the director say as much? How do we know he is not lying?

Allow me an example (a real life one): the artist is a particularly well-respected Philippine sculptor. When I go to his workshop, I don’t see him actually producing his sculptures! It is his assistants who handle the material, and shape the final product. Who is the artist here? Even though these underpaid apprentices used the artist’s “vision”, shouldn’t the value of art rely on who made it in the first place? Can we ignore the artistry of these mere “employees”? Now most of the critics of his work don’t know that he works this way. They rely on his “signature” to appreciate these artworks. They’ve made valid cases for them. What if they found out this is how the artist actually works? For me, it is enough that I know that the object in question was made by human beings. To hell with knowing whoever’s signature is on it when first acknowledging it as art. Auteurship, for me, extends the critical appraisal of an object. It is not the starting point.

“Your understanding of the word auteur is too literal, it’s an abstract concept for the original generating force authoring the distinctive identity of the artwork (which is more important to Art than its craft materiality). So the “Auteur” could very well be a duo or a team, but a team of auteurs then, not a group of mere creative individuals (who each have no idea of the final achievement of the whole outside of their own contribution).”

See disclaimer above. I always begin with the literal essence of something, and then move from there. That’s how I work. And it’s very clear that I deviate from the auteur theory with regards to the value of art being dependent upon the identity of its auteurship, its signature, so to speak. I don’t care whose signature it is. As long as it is art. The intrinsic value, for me, is always the most important, and for me it applies to all artforms. See the above with regards to anonymoust art.

Unfortunately, I don’t see how your Lynch example is a very good example…

“The point is that he knows and that he will control all contributions in order to accomplish this vision.”

Whenever I try to apply this to film, it seems insufficient. Is such fascism even possible? Really, all? Each single gesture, utterance, quality of breath, depth of voice of the actors? Each thread, embroidery, tassel of the costumes? Auteurism is easy when applied to literature. The poet, for example, is supposedly responsible for every punctuation mark, linebreak, tenor, vehicle, metaphor, and word of the poem. (Of course, there could be other forces at work – Ezra Pound is as much the author of The Wasteland as Eliot). The poet is clearly and obviously the autuer. How is this possible in film? Costumes, props, sets, acting, editing, camera movement, negotiation of space, etc. Can we really answer who is the auteur? I’d rather ask: how is this art?

“Auteurism isn’t a numerical rule, it depends on the identity of the signature, whoever authored it.”

It just struck me that auteurism is very passe when applied to the other arts. What is with the obsession with the identity of the artist? That’s why a Picasso costs a million dollars when in fact it should have no monetary value but simply possess its artistic value… But that is another discussion. Sorry for being tangential.

I know, I’m being frustratingly literal. Ah well 🙂 I just keep on blabbing… I need to stop. I need to take care of the baby!

Maya is much better at expressing my thoughts anyway. Harry, I also hope that you don’t think I’m being deliberately antagonistic! All my arguments spring from love.

Adam K

April 1, 2008 at 9:14 pm

Long-time reader, first-time commenter, so bear with the long post.

Sarris in “Toward a Theory of Film History,” the intro to The American Cinema, writes,

“Ultimately, the auteur theory is not so much a theory as an attitude…The auteur critic is obsessed with the wholeness of art and the artist. He looks at a film as a whole, a director as a whole” and

“[t]he auteur theory should not be defended too strenuously in terms of the predilections of this or that auteur critic” and

“The transcendental view of the auteur theory considers itself the first step rather than the last stop in a total history of the cinema…[it] is merely a system of tentative priorities, a pattern theory in constant flux.”

I cite this not only because I have an American Cinema 40th anniversary blog-a-thon coming up on the 14th (plug!), but because it backs up Adrian’s “holistic” def of auteurism as well as situating it as an interpretive, reading tool rather than a simple exaltation of the director at the expense of craft and collaboration.

It just so happened that Renoir, Ford, Hawks, Ophuls, et al. each made films that Sarris loved; it’s the films themselves, considered in groups as well as wholes, rather than the individuals behind them, that led him and the French and everyone else to examine those who may have had a hand in the films’ creation. Sarris states in “The Auteur Theory Revisited” that he wishes he had put more polemical emphasis on “the tantalizing mystery of style rather than on the romantic agony of the artists,” and although I think the study of mise en scène was obviously what he was always after, some others have definitely made this same mistake of emphasis. Polan’s assertion than an auteurist wants “to classify and give distinction to films according to their directors” then seems backwards to me, because great directors have always been ones that make great films, not the other way around. Finally, Andrew asserts that the theory “is one of several methods employed to unify these bits and pieces [of films] into central ideas.”

I’ve been gearing up for the blog-a-thon, sorry for the Sarris-heavy comment, but I think he’s worth revisiting in order to discuss the worth (or worthlessness) of the auteurist and auteurism in the 21st century. In some ways I think the entire concept has run amok since 1968, wildly overpraising the director-as-auteur-as-personality while giving a useful focus to cinephiles and critics. To discuss how a new film fits with the previous director’s is a given critical strategy today. Yet with the exceptions of Hitchcock and Welles, all of Sarris’s Pantheon Directors (and most of the Far Side of Paradise and Expressive Esoterica) had passed on or quit making films by ’68. Auteurism made sense, both for the French and for everyone else, as a method of historical (re)evaluation and taking stock of film history rather than as a hierachy of the here-and-now and a predictive function. Has it run its course in relation to the “classic” Hollywood system that the Cahierists and others lionized? Is the director-centric attitude in its wake, which may have helped allow the movie brats of “New Hollywood” gain traction in the 60s and 70s, still useful? Can it gain new hold in analyzing a mainstream American cinema that may seem even more corporatized and homogenized than its golden age counterpart?

weepingsam

April 2, 2008 at 1:07 am

It’s probably relevant, somehow, that I remember Josh Olson himself getting into arguments over auteurism in other online forums a good ten years ago…. The subject get kicked around a lot, but doesn’t seem to settle anything. I suppose that’s normal: it’s an amorphous subject, and a lot of the issues raised are perennial problems with thinking about films, so it’s not likely to be settled. I’m not sure what I would add to the conversation, but I definitely feel like I need to post a disclaimer when the subject comes up… So – this is mostly just that: a disclaimer….

I think:

1) that film is a composite art – and the arts that make it up can all be considered on their own merits, with or without reference to the film as a finished whole. Ditto the artists who work on a film. (When it comes to film, the answer to Harry’s line “If there is no artist at the origin of the work, there is no Art” might be, in most films there are 50 or more artists and hundreds of craftsmen. Trying to pin film down to one artist isn’t too helpful.)

2) On the other hand – if you consider a film as a whole – you may or may not find a consistent, coherent artistic vision. Which means – an identifiable and analyzable style that exists apart from the film. When you do – it usually belongs to the director, though not exclusively. Producers, writers, performers, even source material (Shakespeare – Stephen King) can function that way.

3) The most useful way to think about “auteurs” is as a kind of genre. Ozu films are more like Shakespeare films or the melodrama of the unknown woman, then anything else. Which really means – biographical and psychological considerations of “auteurs” are not very helpful; the romantic notion of the auteur as a heroic artist is not very useful. Its better to look for what the films have in common – what stylistic, thematic, production, etc. traits can be identified and analyzed. When identifiable patterns coincide with a specific filmmaker, that’s when you have an “auteur”. (Though there’s no way I would use the word itself for it: too much baggage, too many bad analogies,and too much Roland Barthes.)

4) Taking films as a whole, this happens most often with directors – usually directors who do a lot of the work themselves (writing and directing – Chaplin to Bergman to Godard to Wes or PT Anderson), or had significant control over the process (Ozu or Capra or Hitchcock or Hou Hsiao Hsien, etc.) But it can happen with other functions, whether through control of the production (Douglas Fairbanks or Val Lewton) or a strong, identifiable voice (Charlie Kaufman scripts) or even just an element that binds groups of films together, into a kind of genre (Busby Berkeley or Fred Astaire; Stephen King adaptations; Batman films.) It bleeds into genres as such…

5) And – there is no need for their to be only one “auteur” per film. A western can be a comedy, a horror film can be a kung fu movie, so why can’t a Val Lewton film be a Jacques Tourneur film?

I don’t know how important it is to have this category of artist to talk about; but it does seem to work. I mean – it seems very much justified to talk about Ozu’s films or Wes Anderson’s films – or Charlie Kaufman’s, or Val Lewton’s… There are identifiable elements shared by the films – they can be described, analyzed, interpreted, etc. A group of films can generate and illuminate an individual films – just as component parts of a film can be analyzed as complete realized works of their own (I think they can), films can be seen as part of a body of work. Tracing the style, themes, approaches of a filmmaker across films is a very useful process.

Anonymous

April 2, 2008 at 4:29 am

Girish says, “My recent immersion in Indian popular cinema has shown me that auteurism is quite a limiting way to enter that cinema. Genre and stars are at least as, if not more, valuable ways to personally make sense of, e.g. ’70s Bollywood cinema. So, I often end up foregrounding them more than I do the director.”

Which reminds me of Rosenbaum’s anecdote about Marilyn Monroe on a_film_by a couple of years ago, in a similar discussion.

HarryTuttle

April 2, 2008 at 9:56 am

Sorry for the endless comments, Girish, but you’ve opened the can of worms… 😉

Dottie, I don’t think you’re an “ignorant fool”. You define yourself from principles of New Criticism and that’s this conception of criticism I argue with. 😉

I don’t think there is as much antagonism between New Criticism and Auteurism as you may think. The only major difference is the intentional fallacy, i.e. ignoring any background information outside of what we see on screen. But both consider the film a work of art, and ask themselves roughly the same questions (nobody says New Critics aren’t critical, but their scope is self-limited), they just don’t give credit to the same causes.

I didn’t mean “love” to be the analogue in my poet metaphor. It was the proxy relation of the recipient to the author through the object. The New Critic focuses on the object, the Auteurist prefers to contextualize with an oeuvre. But Auteurists don’t necessarily develop a personal fetishist relationship with the actual person behind the signature name (if they do they are misled critics and it did happen to the Young Turks btw).

If we keep going at the meta-free-for-all (Colbert trademark) allow me to use an iceberg metaphor instead. The Auteurist will strive to imagine how the entire iceberg looks like, to inform and nurture the understanding of what is visible. Yet both walk on the same tangible surface, none can access the non-visible depth directly (even the artist himself might not). The New Critic only considers the surface, intentionally restricting the domain of expertise (so “superficial” wasn’t derogatory in my mind).

And if the middle of the surfacing iceberg is submerged, leaving 2 separate “islands”, only the Auteurist will guess they belong to the same body by connecting the dots.

How do New Critics consider a trilogy (which can only make sense in terms of transversal coherence of distinct artworks because of the same vision of the same author)?

re: anonymous art.

If we don’t know the DNA of the actual author, we still know someone had to produce this artwork (like you say), whoever it was, that is the abstract “Auteur”, and we just name it “Shakespeare”, by convention.

People argue Shakespeare didn’t write his plays, who cares? The point is that whoever wrote these plays (Joe or Jim, man or woman, one or several writers) is the abstract Auteur. Auteurism is interested in the personality and inspiration of whoever make the art possible, the administrative identification and the DNA (to figure out who that person was for sure) doesn’t influence the theory we might develop about the signature of this “artist entity” giving birth to the piece of art, about his vision, his world view, his patterns, his motivations.

And in this, Auteurism agrees with New Criticism that what matters in art is the work actually done (the evidence on screen), not the talking points of its creator (or his personal life).

Your sculptor example isn’t a shock, most artists have always worked that way. It doesn’t change the definition of “artist”, nor our analysis of the job.

Do you realize that Michelangelo didn’t paint the ceiling of the Chapel Sistin by himself? Renaissance painters only painted the faces and hands, the rest was relegated to their disciples under their supervision.

Christo didn’t warp up the Reichstag by himself. But nobody doubts that without him we would never have seen that happening. That’s the artist’s intention. The operative realisation of the material artefact is secondary, critics don’t even have to worry about it for the simple reason that whatever the individual workers did right or wrong (at the scale of their contribution) during the construction will never alter the nature of the final idea by any means. It would be very narrow to limit Art to notions of skill, sweat, or time spent on an actual realisation.

And I disagree with Maya who assumes Nature creates art by itself. It does matter a great deal to figure out if an artefact we find was made by a conscious mind or was the result of natural phenomena. Maybe it doesn’t matter in terms of aesthetics (appreciation of Beauty in the universe), but it matters to critics (thus the History of Human Arts) who only criticize the effort put in the work by an artist. Nature doesn’t need to be criticized…

I hope we are not defining Art from its price market either (it’s only a commercial speculative exploitation, at best a result of the aesthetical value critics put in it)!

I didn’t mean to be demeaning when I said the average audience is “blissfully ignorant”, it is a coveted state of viewership (think of it as “unspoiled” by pre-knowledge).

Though when we talk about consumerism and Art, we have to make the levels of contacts with the film stand out, and qualify their respective commitment.

“How would you know if an employee fails? Does the director say as much? How do we know he is not lying?”

I’m just saying employees, however creative they are, are replaceable. The fact a cinematographer lensed the first half and another shot the rest (which happens a lot with secondary unit shooting) is of lesser importance since the auteur piloted whoever was holding the camera to get things done the way he wants them. If the auteur thought the change in skill and style would alter his project too dramatically he wouldn’t let it happen. That’s why we don’t have to question such details (unless we investigate the reasons of a flop), and we only judge the auteur’s intentions on whatever he decided to greenlight to be shown publicly, he therefore endorses (and appropriates) all mistakes and contributions made during the shooting.

HarryTuttle

April 2, 2008 at 10:20 am

The main reason why La Politique des Auteurs denied to screenwriters a right to authoring a film wasn’t (from my understanding) because an auteur had to be alone and had to be the director, but because the position of a screenwriter within the production of a film (the level of commitment to the final result on screen) doesn’t make him/her an auteur or co-auteur. The point was to split off with the inappropriate model imported from Literature and Theatre where writing is the source. In cinema, writing isn’t THE major source of creation of the essential mise-en-scene.

If a screenwriter (or a producer or an actor) does participate in mise-en-scene (in a strategic notable way), by blocking a scene, by developing the cinematic language, then maybe they become auteur too. But dialogue alone, however great, only make you an author of Literature, just like a great costume, makes you an author of Couture, not an author of Cinema. 😉

girish

April 2, 2008 at 11:35 am

Thank you, everyone!

Harry, don’t apologize–discussion is what this space is meant for!

Anonymous

April 2, 2008 at 3:34 pm

Perhaps someone here could explain this so I can better understand at least some aspect of the auteur theory.

Taxi Driver is widely acknowledged as a film by Martin Scorsese.

However, as far as I can ascertain, Scorsese was hired to direct it by producers who thought Paul Schrader’s script would make an interesting film.

One memorable scene in Taxi Driver is the overhead shot of Travis’s hand sweeping over Betsy’s desk in the campaign office. Scorsese once said in an interview that he didn’t like the shot because it looked like something out of a Robert Bresson movie, but he filmed it simply because it was in Schrader’s script.

Maybe I’m missing something, but how could it be a film “by” Martin Scorsese if he’s essentially at the mercy of the producers and Schrader’s screenplay?

Adam K

April 2, 2008 at 4:51 pm

anon, I consider TD as least as much a film by Paul Schrader and Robert De Niro as by Scorsese. There need not be one single auteur to a film. Jonathan Rosenbaum goes into detail about the various competing strands of Taxi Driver here at the Reader Archive, and he even includes Bernard Hermann as a composing auteur.

Anonymous

April 2, 2008 at 5:30 pm

Well, Harry, just a few more words, since I think I’ve been rambling on for too long, and I’m sure there must be a couple of people here who are already sick of me!

First, you have to know that my appreciation of art does not end with New Criticism. It is simply the foundation of how I approach objects (particularly objects whose provenance is unknown, say, a sculputure by an unknown artist and without much cultural or chronological context, a lot of postmodern works really – how to judge such a thing?). Of course I agree it is limited, but I think it is very useful. If the object does not hold up under such simply scrutiny, how can it in other frameworks?

Even if it ends there, I’d have to say that is sufficient in and of itself – such an object is by that simple standard already art. I do not find it superficial at all. But when we move towards other contexts, then the understanding of the object is further enriched. Moving away from New Criticism, which, I think, does not treat the object superficially at all, the appreciation of an object is simply further enriched. Maybe it is a matter of perspective, but I don’t find New Criticism limiting at all. Of course, that’s easy for me to say since I wouldn’t consider myself a “New Critic”. I’d call my approach eclectic or weird or even undisciplined, but, oh well, I find that it works!

My argument for the sake of “employees” I’d have to admit is really more of a personal bias than anything else. Why aren’t they given credit at all? In our examples wherein the artists aren’t directly involved in the actual creation of their art, why must these people go unnoticed? Who are the other people who painted the Sistene Chapel? History has forgotten them. We have forgotten them. That is a terrible thing, in my opinion. Is Michelangelo somehow more important than them because it was his vision? I personally doubt it. Without them, there wouldn’t be a Sistine Chapel! Again, this is a personal reaction more than anything else.

“It would be very narrow to limit Art to notions of skill, sweat, or time spent on an actual realisation.”

Ah, but without these things art isn’t even possible. It would be narrow to limit the idea of art to these things, indeed, but to ignore that they are an integral and fundamental part of art is not a good thing either. They are necessary to art, so for me they are a part of art. A body needs its organs to exist.

“And I disagree with Maya who assumes Nature creates art by itself.”

I don’t think he said as much. The way I read it (the last sentence in the paragraph), it’s just him taking his statement on art to the extreme. Sort of like what Duchamp did with his infamous toilet or what Japanese artists achieve with suiseki. It’s the best statement on art I’ve read, in my opinion.

Harry, I take it you do not take kindly to postmodernism? (The intentional fallacy figuring into it prominently). Just a bit of levity there… 🙂

Anyway, I take my leave of this thread. I’ve taken up too much of everyone’s time already. Kisses.

Anonymous

April 2, 2008 at 5:39 pm

Oh, just a little bit of glance back. Girish, to answer your question, auteur-wise I find the stars of the Hollywood studio system as much the auteurs of the films as the great directors they worked with. I’m thinking of Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, Errol Flynn alongside the likes of Frank Borzage, George Cukor, and Raoul Walsh.

Davis, the Marilyn Monroe anecdote is wonderful. And Adam, thank you for pointing out another lovely piece by Mr. Rosenbaum. It reminds me of another unsung auteur of classic Hollywood cinema: Edith Head.

girish

April 2, 2008 at 7:11 pm

All–There’s a terrific interview with Pedro Costa at Greencine, by our own Maya.

Dan Sallitt

April 2, 2008 at 9:18 pm

Thanks for quoting my post, Girish. I should mention that it was written in a moment of doubt about my vocation, and that I found afterwards that it was impossible for me to change my auteurist mindset in any fundamental way. So these days I simply use those ideas as a check on my wilder auteurist impulses, a moderating influence.

It’s true that discussions about auteurism tend to be unsatisfying, because everyone has different ideas about what’s at stake. I would like to make one observation that I don’t believe has been mentioned in this thread: namely, that there are historical justifications for regarding auteurism as an aesthetic and not as a theory. That is to say, in the periods in which auteurism has flourished, it has been strongly identified with a mission to promote one set of filmmaking gods and demote another set. My feeling is that not everyone should be an auteurist: that auteurism is basically a way of codifying what you like and what you don’t like. The fact that the auteurist “what you like” is strongly associated with the practice of direction is probably best regarded as a corollary rather than a central theorem.

Of course, it’s difficult, maybe impossible, to theorize about whether works of art are good or bad. But I do believe that that’s the context in which auteurism is meaningful, the context in which it’s perhaps more than just a lens or a tool.

Michael E. Kerpan Jr.

April 3, 2008 at 2:37 am

I guess I am a hardcore directorial auteurist. As I see it, while a first-rate director can make a first-rate from a so-so script, a mediocre director is not likely to make a first-rate film from even an excellent script.

To me, cinema is ultimately all about vision. And the writer of a script (unless he is also the director) plays no real role in determining just what we get shown in a film. (I am more interested in the theoretical possibility of cinematographic auteurism).

That said. There are certain screenwriting credits that have a sort of brand value. Almost the only truly major films made by Kon Ichikawa were those written by his wife Natto Wada. She seemed to have the ability to write scripts that Ichikawa proceeded to infuse with visual genius. Once she retired, his sense of vision atrophied. Why? I haven’t a clue.

Another example — a script credit by Yoko Mizuki (who wrote scripts for Naruse, Imai, Yoshimura, Kobayashi et al.) definitely makes me take extra interest in a film. Interestingly, she is one of the few people (other than Wada) who managed to write a script for Ichikawa that resulted in a first-rate film (Ototo).

I tend to favor the earliest version of auteuist analysis — which utilized the notion as a hypothesis to be explored with regard to the issue of whether particular directors could be viewed as the ultimate creators of their works.

Finally I would note that most of my favorite directors had (or have) remarkably stable creative teams — routinely working with the same writers, cinematographers, art directors, performers, etc. So designation of a director as an auteur should not lead to overlooking the contribution of the other important members of the team that participates in making a great film. One thing I love about Ozu (as director and man) is the fact that he insisted on being introduced to each and every new staff member at the outset of making each film — and then addressed them by name (in polite form) from that point on.

HarryTuttle

April 3, 2008 at 12:50 pm

Topical audio podcast, this week at NewYorker : Cinema Revolution, Richard Brody talks about Jean-Luc Godard and the Nouvelle Vague auteurists. 😉

Michael Guillen

April 4, 2008 at 6:50 am

Thanks for the tip of the hat, Girish. You’re so generous.

Well. I go away for a few days and the joint runs riot. I got through the Polan article, Girish, and now I have a flock of hand-folded cranes, a couple of boats, some planes, and a prancing Blade Runner unicorn.

Juss jokin’.

Actually, it’s a well-written, accessible essay and I thank you for linking to it. There’s so much to read out there on the Internet that it’s nice to have some guidance now and then. Almost immediately I was able to spot Polan’s definition of the contemporary auteur in the press notes describing director Rob Minkoff for The Forbidden Kingdom. This ain’t your daddy’s auteurism! But I certainly empathize with Polan’s caution that continuing the classic auteur tradition uncritically is perhaps the least interesting approach of all and might invoke a spirit of diminishing returns. I’ve likewise come to fully appreciate the timeliness of your bringing the subject of auteurism up on the eve of the May ’68 anniversary. It’s a valid time for review for the role of auteurism in the cultural revolution of that time, let alone the revolutions it inspired. That being said, my eyes start to glaze over when we begin reading about writing about writing; it becomes too “meta” for me. Talk about distanciation! I’d rather go watch a movie.

“I disagree with Maya who assumes Nature creates art by itself”—which, of course, I never said, Harry; but, little cattle little care. I said that the forms of nature can be perceived as artistic; that the indigenous artifact can be interpreted as artistic; and that the “artistic”—dependent upon the white cube; i.e., any given moment in culture—can be elevated to the definition of “art” that you’re creaming your jeans about. I’m glad to hear you say that nature doesn’t need to be criticized. Perhaps I can seek refuge there?

Michael, I like your honest defense of hardcore directorial auteurism. You claim your tools lovingly and with responsible awareness of how you can use them to understand the directors you favor and how they, in turn, have been responsible to their creative teams. That’s very well stated.

girish

April 4, 2008 at 2:48 pm

Thank you, Dan, Michael K., Harry and Maya, for your thoughts and for gamely continuing this discussion!

girish

April 4, 2008 at 3:22 pm

Errol Morris has a huge blog post at the NYT. Let me excerpt some interesting bits:

“Memory is an elastic affair. We remember selectively, just as we perceive selectively. We have to go back over perceived and remembered events, in order to figure out what happened, what really happened. My re-enactments focus our attention on some specific detail or object that helps us look beyond the surface of images to something hidden, something deeper – something that better captures what really happened. […]

[on The Thin Blue Line]: “Critics don’t like re-enactments in documentary films – perhaps because they think that documentary images should come from the present, that the director should be hands-off. But a story in the past has to be re-enacted. Here’s my method. I reconstruct the past through interviews (retrospective accounts), documents and other scraps of evidence. I tell a story about how the police and the newspapers got it wrong. I try to explain (1) what I believe is the real story and (2) why they got it wrong. I take the pieces of the false narrative, rearrange them, emphasize new details, and construct a new narrative. I grab hold of the milkshake as an image because it focuses the viewers’ attention and helps them to better understand what really happened. The three slow-motion shots of the milkshake – the milkshake being thrown, its parabolic trajectory through the night sky and its unceremonious landing in the dirt at the side of the road – are designed to emphasize a detail that might otherwise be overlooked and to focus attention on where Turko was and what she saw. […]

“Critics argue that the use of re-enactments suggest a callous disregard on the part of a filmmaker for what is true. I don’t agree. Some re-enactments serve the truth, others subvert it. There is no mode of expression, no technique of production that will instantly produce truth or falsehood. There is no veritas lens – no lens that provides a “truthful” picture of events. There is cinema vérité and kino pravda but no cinematic truth.

“The engine of uncovering truth is not some special lens or even the unadorned human eye; it is unadorned human reason. It wasn’t a cinema vérité documentary that got Randall Dale Adams out of prison. It was film that re-enacted important details of the crime. It was an investigation – part of which was done with a camera. The re-enactments capture the important details of that investigation. It’s not re-enactments per se that are wrong or inappropriate. It’s the use of them. I use re-enactments to burrow underneath the surface of reality in an attempt to uncover some hidden truth.”

Michael Guillen

April 4, 2008 at 4:08 pm

Methinks the documentarian doth protest too much. Though I’m a great fan of the work of Errol Morris, I was none too fond of Standard Operating Procedure, not so much because of whether or not it should have included re-enactments; but, because the re-enactments struck me as way too horrific. It’s one of the very few times I’ve cancelled an interview because I knew I would be combative, which I don’t like to be when I’m interviewing someone. Besides, what could I ask him to explain that he hasn’t gone on at length about in his blog entries?

HarryTuttle

April 4, 2008 at 5:38 pm

Dottie, I never studied PoMo, so I don’t understand what this is exactly.

From your replies I gather that your conception of “Art” is very much pragmatic, dependent on contingency, tangible aspects while my conception of Art is removed from this materiality, it is human genius, creativity, visionary perception, not in a prosaic way but in a transcendental way.

Actually some of Michelangelo’s “helpers” became great artists themselves when they did their own art, and critics like to point to the blooming touch of the disciple within the scheme of the master. But isn’t usually enough to disown the master’s overwhelming oversight and artistic property.

What does it matter if you ignore the firstname of whoever sculpted the Venus of Milo? A critic is expected to be able to investigate and notice the personality of the person who did it, why he used these proportions, this posture, this facial expression, this technique. It is different from another Greek statue of the same period or the same area and it’s this (unknown) artist’s incarnated vision that makes it unique. You know, it’s not because we know the artist, or that we can even talk to the person directly that we’d get more useful information to help us analyze the work done. My issue with New Criticism isn’t that they ignore the personal psychology of the artist, but that they just see an object and forget about the larger motivation that urges a person to become artist, to share this vision, not only in this object but in a consistent signature.

Maya, if you make a difference between “artistic value” and “art” (which I don’t understand within the context of our discussion), are you saying it’s possible to interpretate something as “artistic” non-critically? And what makes you think you (yourself or anybody’s action) could escape criticism? Without criticism there is no Art. It’s because someone declares, critically, this stuff in our environment is art that objects (or actions) become Art.

I don’t like to call “auteurism” a mere “genre”… a filmmaker is not “auteur” by choice like he would put on a comedy hat, or a drama suit. Genres are horizontal, equivalent optional narrative categories. To be an auteur is not optional. I hope auteurism is not limited to choosing to make “art films”. Either a filmmaker is an artist who knows what he doing, or he’s an employee doing the job he’s asked to do and apply formulae learnt in school. But as far as we consider Cinema an Art, there are only artists making it. There are bad artists and great artists. There are auteurs who have no clue how to exploit and translate their inner personality so they will not be able to inprint their signature in the work they do. But being an auteur is part of the nature of this creative activity, it’s not an alternative.

This polemic around auteurism is less about favoring such or such theoretical approach of an artwork, it’s whether we consider Cinema an Art and filmmakers artists (i.e. auteurs). Attacking auteurism and especially arguing the filmmaker is not in control of everything that there are many contributors is always denying cinema it’s status of Art equivalent to Literature and Paintings.

Michael Guillen

April 4, 2008 at 5:51 pm

Harry, the fish aren’t biting today. They’re enjoying their own nature.

edo

April 4, 2008 at 7:46 pm

To seize upon this notion of ‘wholeness’ as integral, if not essential, to the auteurist quest…