The new issue of Cineaste opens with a hot mess of an editorial titled “Cancellation Culture.” (Here is the PDF link.)

Last month, following a protest by the Black Students Union, Bowling Green State University in Ohio voted to rename its campus theater originally named for Lillian and Dorothy Gish. The students had objected to the name because of Lillian Gish’s starring role in D.W. Griffith’s famously racist film The Birth of a Nation (1915), and because of the heightened racist forces at work across the country at this moment.

The editorial narrates this incident, following it up with a discussion of Amazon’s decision to pull the plug on its distribution deal with Woody Allen. Lamenting these events, the editors make the claim that “cancellation culture” is causing people and artworks to be “vanished”; that film culture is “discarding what came before,” “wiping away the past,” and “erasing history.”

Let me first say that I have some sympathy for those defending Gish: she did not write or direct The Birth of a Nation, and there is no evidence that she was in any way responsible for the abhorrent racial beliefs advanced by the film. [EDIT: I take that back. See here and here.] Nevertheless, there are at least two crucial flaws in the Cineaste editors’ argument.

First, the totality of effects produced by a film—upon viewers and the culture at large—cannot be ascribed solely to a single individual, the director. Even traditional auteurism knows and acknowledges this. Gish, as the visible, charismatic and narratively important star of the film, has helped in no small degree its ascent to the canon.

But the much more significant problem with the argument is this: No one has called for any kind of boycott on watching or writing about Lillian Gish movies. Many of Gish’s films, especially the ones she made with Griffith, have been and continue to be available on DVD. There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that the hundreds if not thousands of extant copies of these DVDs—as well the scores of articles and books that study or reference Gish’s films—will “vanish.”

In fact, even in Woody Allen’s case, where there has been a much more widespread call to not support the work, let us note that his enormous filmography continues to be easily accessible on DVD or streaming—as is the large volume of writing on his films both in print and online. What’s more, no less a mainstream outlet than HBO recently added a retrospective series of Woody Allen films to its streaming lineup. Sorry: I don’t see a whole lot of erasure happening here!

What is disturbing about such claims of erasure is not only that they are overblown. They are in fact insidious, because they represent a powerful pushback against any attempt by marginalized voices to call the film canon—installed overwhelmingly by white cismale critics and scholars over the last century—to account.

The Cineaste piece reserves its worst offense for its closing, when the editors complain: “It’s no coincidence that these movements [#MeToo and Black Lives Matter] coalesced in the age of Trump, a President who languishes in the eternal present…” This breathtaking equivalence of women’s and Black people’s protests with Trump’s actions is not only profoundly insulting, it’s also ignorant. It is precisely the acute historical consciousness of oppression that drives the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, not the Trumpian whims of an “eternal present.”

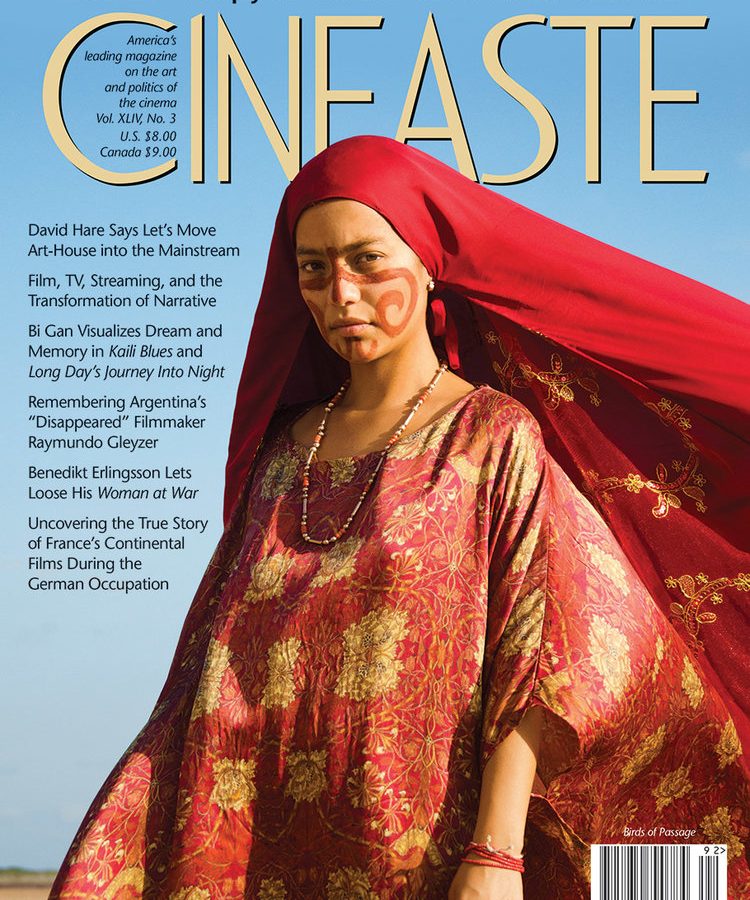

What could possibly account for this wrong-headed, out-of-touch editorial? A glance at the masthead offers a clue. Of the 9 people listed as “editors” (not including assistant editors), there is just one woman, and only one person of color. White men dominate the magazine: the current issue is 86% white men (31 out of 36 pieces). The average over the last year and over the last three-year period are both close to 80%.

Let me end by saying: I have been a Cineaste subscriber for years. I value the magazine, and I admire many of its writers. As a loyal reader, I want to issue a public call to the magazine to diversify its editorial collective—significantly!—and do the same for its ensemble of writers.

Each issue of Cineaste has, emblazoned upon its cover, the following words: “America’s leading magazine on the art and politics of the cinema.” It is simply not possible to run a credible film magazine today—let alone one that is self-avowedly political—without putting gender and racial equity front and center. A commitment to politics rings hollow without an accompanying commitment to representational equity and justice.

For stimulating conversations, I want to thank my friends Erika Balsom, Elena Gorfinkel, and Tanya Loughead.

A word on the stats: In counting up the pieces published in the magazine, and computing the average % written by white men, I included all writing except editorials, staff recommendations of films, and symposia.